Blog:

In other words

15 tips to proofread your own writing—Part 2

In my previous article, I shared my first 5 proofreading tips with you on how to find errors and inconsistencies in your own writing.

In this second part, you’ll discover my Tips #6–10 to help you spot mistakes and discrepancies in your work, including punctuation, numbers, references and quotes, figures and tables, and knowing your writing habits and mistakes.

Ready? Let’s dive right in!

Tip #6: Check punctuation

Punctuation is important because it indicates pauses and emphasizes the thoughts and ideas in our writing. It also drives the rhythm and flow of a text.

There are many resources on the correct—and optional—use of punctuation in English.

For example, the Chartered Institute of Editors and Proofreaders (CIEP) has an 84-page guide on punctuation. It is a condensed version of the many aspects to consider—beyond periods and commas and the occasional semicolon.

Don’t worry—I’m not saying you must buy books or guides and dive into the nitty-gritty details of grammar rules and sentence structure. It’s not everybody’s cup of tea.

But if you love learning about the English language and want to spend time to refresh and expand your knowledge on this topic, I highly recommend you add those resources to your library (see also Tip #15).

The advice I share here is actually quite simple and mostly involves consistent usage of punctuation.

Here is a non-exhaustive list to guide you when checking punctuation in your writing:

- Do all opening quotation marks have a closing pair?

- Do all opening brackets or parentheses have a closing pair?

- Are you using double quotation marks for U.S. English and single quotation marks for British English? (But: Use single quotation marks for a quote inside a quote in U.S. English and double quotation marks for a quote inside a quote in British English. They don’t make it easy, do they? See also Differences between British and American English

- Are you using hyphens correctly and consistently?

- Are you using an en dash (–) for date ranges, such as “2006–2008”, rather than a hyphen (‑)?

- Are you using em dashes (—) correctly, such as in empty cells of a table?

- Are you using minus signs for negative numbers rather than hyphens or en-dashes?

- Are you using serial commas? You don’t have to, but at the very least you need to place them where they are necessary for clarity. For example, the following sentence needs a serial comma: “George went to church with his parents, Sister Mary Clarence, and the Archbishop of Canterbury.” Without that final comma, the reader might think that George’s parents are Sister Mary Clarence and the Archbishop. Now that would be awkward, wouldn’t it?

- …

PRO TIP: Check the punctuation in your writing as best as you can with the knowledge and resources you have. The more punctuation errors and inconsistencies you can correct yourself, the more money you can save on a hired editor or proofreader.

Tip #7: Check how you display numbers

You probably mention numbers somewhere in your text, whether you are working on an academic paper, a blog article, a job application, or a novel.

How do you treat numbers in your document? Do you use a consistent style?

It’s always a good idea to check with your publisher, supervisor, or academic institution about their preferred style and whether they have any author or student guidelines for you to follow.

Here are some examples of what you should pay attention to regarding numbers:

- Words vs. numerals: Do you write out numbers one to ten and then use numerals for 11 and up, or do you apply a different style?

- Times: Do you use a.m. and p.m. or the 24-hour clock (for example, “11.20 p.m.” or “23:20 hours”)?

- Dates: Do you use the British style (for example, “31 January 2020”) or the U.S. style (“January 31, 2020”)?

- Centuries: Do you write out centuries (for example, “thirteenth century”), or do you use numerals, either with superscripts (“13th century”) or without (“13th century”)?

- Percent: Do you write the percent symbol, or do you spell it out (for example, “58%” or “58 percent”)?

- …

Again, a style sheet (see also Tip #3 and my article on style guides) is useful here to help you keep track of all your decisions regarding numbers.

PRO TIP: There are different ways to style numbers. If you’re working with a journal or publisher, check what it says in their author guidelines regarding a preferred style. In any case, regardless of the type of document, you should present numbers consistently throughout your text.

Tip #8: Check references and quotes

References and quotes are important, and you need to know how to display and cite them in your work correctly.

Let’s talk about references first. There are several aspects you need to consider:

- Do all in-text citations appear in the bibliography?

- Similarly, are all references in the bibliography cited somewhere in the text?

- Do the publication years for in-text citations match the publication years in the corresponding reference in the bibliography?

- Are all in-text citations styled correctly and consistently (for example, according to the APA Style, Chicago Manual of Style, Vancouver style, IEEE style)?

- Are the cited references appropriate in the given context? For example, if you cite “Smith et al. (2006)” in reference to food shortages in West Africa in the late 1990s, but the authors studied Thailand’s rice exports in 2003, then you’ll have to revise that citation.

For academic texts, I highly recommend using reference management software, such as Mendeley or Zotero, to help you organize and cite references in your work.

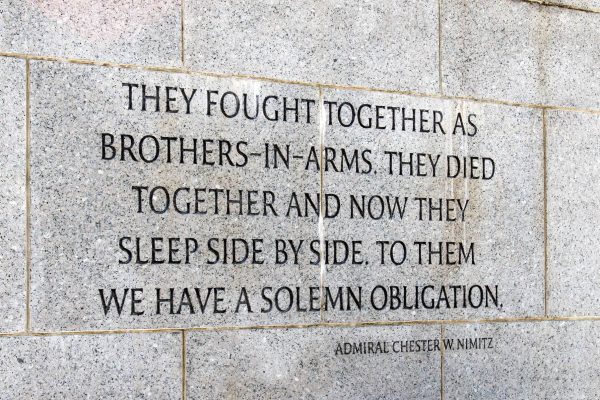

Moving on to quotes: If you use any in your text, take the time to verify that the wording, punctuation, and grammar in the quote are the same as in the original.

For example, if you’re writing your document in U.S. English but the person you’re quoting used the British spelling in their text, don’t change it.

Similarly, if there’s a spelling, punctuation, or grammar error in the original, leave it in the quote.

The source text must be preserved in its entirety.

Make sure to put the entire quote inside quotation marks, except when using longer quotes, which are usually presented separately from the main text.

Remember that U.S. English uses double quotation marks, while British English uses single quotation marks. (But: U.S. English uses single quotation marks for a quote inside a quote, while British English uses double quotation marks for a quote inside a quote. See also Differences between British and American English.)

Always include the source immediately next to or beneath the quote.

If you’re uncertain about the referencing style or presentation of quotes in your thesis or dissertation and want a professional to check them for you, I can help. I specialize in academic texts and am well-versed in the correct use of various citation styles.

PRO TIP: Use a reference management software program to organize your references. Make sure that any direct quotes are the same as in the original. Finally, cross-reference your bibliography with your in-text citations to ensure your list of references is complete.

Tip #9: Check figures and tables

If you’re using diagrams and presenting data in your writing, it’s easy to get lost in the details and forget about the reader and whether the displayed information makes sense to them.

There are many aspects to consider when working with figures and tables, so you should work methodically here, too.

Below are a few questions you can use as a checklist (note that this list is not complete).

- Do you refer to each figure and table in your text somewhere?

- Do all figures and tables you refer to in your text appear in the proper places and in the correct sequence?

- Does the attribution in your text match the figure or table you intend to reference? For example, if Figure 2 shows a flowchart of how you answered your research question, but you refer to Figure 2 for the frequency distribution of your findings, then you’ve got your figures mixed up.

- If you have a map in your text, does it have all the information to understand it, such as a caption, a legend, a scale bar, and a compass north?

- Do the percentages for each dataset or group add up to 100%? If not, do you explain somewhere why the remaining percentages are not shown?

- Is there enough information in the tables and figures for the reader to understand them without having to read the main text?

- Do you have a list of figures and a list of tables at the beginning of your document?

These are only some of the many aspects to consider. Depending on the type and length of your document, it may take you several hours to check all figures and tables, so make sure to set aside enough time for this part.

Always try to put yourself into the mind of the reader and ask yourself whether the information you present is clear and easy to understand. Having a second pair of eyes for this—a friend, a colleague, or a professional—is particularly useful.

PRO TIP: Focus on your tables and figures in a separate pass rather than checking them while you look for spelling and grammar issues. The data you display in tables and figures must make sense to the reader and be easily understood without them having to read the whole paper. Get a fresh perspective from another person if you can.

Tip #10: Know thyself … and thy common mistakes!

Familiarizing yourself with your writing habits helps you to look for and correct your most frequent writing mistakes.

Perhaps you tend to …

- confuse their with they’re?

- forget where the apostrophe goes in possessives, such as in clients’ and client’s?

- mix up the different spellings or meanings in British and American English?

- translate expressions in another language directly into English?

- overwrite?

- underwrite?

If you don’t know your writing habits yet, the best way to find out is to receive feedback from another person. Ideally, this is a native speaker in your document language who is also a skilled language professional.

Sometimes you may not even realize that you’ve been misspelling certain words or using an incorrect expression—until someone tells you or you learn about it elsewhere (see also Tip #15).

Therefore:

Write. Revise. Get feedback. Revise.

Rinse and repeat.

The more you write and revise—and the more professional feedback you receive—the more attuned you become to your writing habits.

Seasoned writers will know themselves well enough to identify the weaknesses in their writing and can target their proofreading efforts accordingly.

PRO TIP: The more you write, the more you learn about your writing habits and the mistakes you often make. If you don’t yet know what they are, a professional editor or proofreader can help you.

My proofreading service includes helpful comments on recurring errors in your writing. If you choose my editing service, you’ll also receive editorial feedback with many practical tips for you and what pitfalls to avoid in the future.

Ready for my last 5 tips to help you weed out errors and inconsistencies in your texts?

Check out Part 3 of this series on 15 tips to proofread your own writing!

Christina Stinn is a professional translator, proofreader, and editor with a background in ecological research and experience in publishing peer-reviewed articles in academic journals. She is a Professional Member of the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading (CIEP) and has a M.Sc. degree in International Nature Conservation. So far her work has included fiction and non-fiction books, academic journal articles, and marketing materials in English and German. She loves working with clients who strive to bring their writing to the next level and enjoys taking part in their journey. Find out more

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: